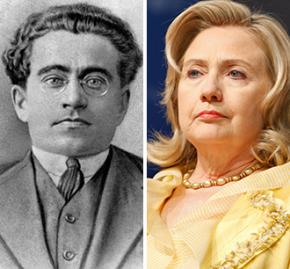

Would Gramsci be #WithHer?

takes issue with an In These Times article criticizing the Green Party's Jill Stein--and with its attempt to claim Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci as an authority.

ACTIVIST AND journalist Kate Aronoff last month wrote a scathing critique of Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein's campaign, accusing her and her supporters of "putting too much emphasis on the presidency and the electoral process itself, while declining to undertake the kind of deep organizing necessary to alter the state of play in these arenas. The result, for the Greens, is a politics too interested in being right, and not enough in actually taking state power."

Aronoff invoked a passage from Antonio Gramsci, a leader of the Italian Communist Party imprisoned by Mussolini, to buttress her case: "It is necessary to direct one's attention violently toward the conditions of the present as it is, if one wishes to transform it."

Aronoff's article and Gramsci's place in it raise two basic questions:

1. What is Aronoff's alternative to Stein?

2. Would Gramsci support her argument?

At first glance, Aronoff appears to be critiquing Stein from a revolutionary point of view. She doesn't make-believe that Clinton's "hawkish neoliberalism" is any sort of solution to Trump's "white nationalism." Instead, she laments that Stein and the Green Party are an ineffective alternative to the "twin evils," as she calls them.

What then might constitute a more effective alternative? One that can win "state power"?

I entirely agree with the first element of the alternative Aronoff proposes--namely, the "social movements from Occupy Wall Street to the DREAMers." Socialist Worker has, of course, long championed the centrality of social and class struggle.

But Aronoff has more to add on this point. "The political revolution the Sanders campaign sparked," she writes, "promises to carry on--both by Sanders...and the movement leaders who increasingly see the Democratic Party and electoral fights as winnable terrain."

Here, Aronoff invites her readers to slide on over from "social movements" to "electoral fights," but offers little explanation for why this makes sense. Who are these "movement leaders," and what exactly can be won on the terrain of "the Democratic Party and electoral fights"?

We can point to victorious Fight for 15 and other minimum-wage ballot measures, but those have often enough been carried out in the face of opposition from Democratic Party officeholders and officials. Insofar as any presidential campaign has championed these movements in 2016, Stein certainly deserves more credit that Clinton.

Meanwhile, Clinton's Democratic Party has held the presidency for 16 of the last 24 years--and looks set to go for at least another four--along with controlling both houses of Congress at various points along the way. Yet this has been the era of neoliberal-New Jim Crow-imperialism par excellence. Stein isn't responsible for any of this.

SO WHAT is the essence of Aronoff's criticism? Stein is challenging the Democratic Party's monopoly on progressive politics--and that interferes with Aronoff's belief that the left has a "real chance to elect hundreds of progressive and even radical leaders to office, and pose a serious challenge to statehouses, city councils and even Senate seats long held by the status quo."

Aronoff forgets to add the proviso that these "hundreds" of candidates must, in her view, be Democrats--or perhaps they might start off as local independents before moving up the political food chain into the Democratic Party, following the example of a certain senator from Vermont.

But this is exactly where things get sticky. Having fought the good fight, Sanders ended his campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination by endorsing Clinton, one of Aronoff's "twin evils"--and went so far as to predict that she would "make an outstanding president." Sanders started by calling for a "political revolution" and ended by supporting the candidate he wanted a revolution against.

Sanders has remained steadfast in his strategic orientation on transforming the Democratic Party. Aronoff appears to agree with him on this point, but perhaps feels he hasn't picked the right down-ballot candidates or has made this or that tactical error.

She wants to fight for a more effective takeover of the Democratic Party, but rather than spelling out exactly how this will be done--and which "movement leaders" will replace the current Democratic Party leaders--she adds her voice to those who want to cast aspersions on those who would take a different political path. Aronoff's rhetorical method is disappointing, because her political point of view is a perfectly legitimate, even if I believe it is a strategic dead end.

I will say that this strategy of seeing the Democratic Party as a vehicle for change in some form--whether articulated by Sanders or Aronoff or others--is hardly a "new" endeavor. Activists entering the Democratic Party to change it--sometimes known as the "realignment strategy"--is an age-old practice, and the repeated outcome of these efforts is why the Democratic Party is known as the "graveyard of social movements."

Another effort along these lines risks ensnaring a new generation of young radicals in the trap that dragged down the Communist Party in the 1930s, when it subordinated its goals to the limits of Roosevelt's New Deal, and many of the best revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s--such as the Black Panthers who signed up with once-and-future Gov. Jerry Brown. Rather than extending their revolutions, they were co-opted and disorganized.

Far better, in my opinion, is to work together in social movements, but simultaneously advocate the need to build working-class independence from the two-party system, even if the political structures for doing so remain embryonic. After all, all adult organisms begin in vulnerable and underdeveloped forms before passing through the various stages of infancy, youth and maturity--all the while taking care not to get hit by a car.

Stein's campaign is not, as Aronoff would have us believe, a "Sisyphean campaign and a few minutes in the voting booth every four years for revolution." It is, rather, one part of the fight to build something that can confront "hawkish neoliberalism," "white nationalism" and a whole host of other features of capitalist property relations and the state that guards over them.

In the end, Aronoff never concretely answers the question of who people should vote for in November. If she were advocating for a principled abstentionist position in favor of militant grassroots activism, that would be one thing, and then perhaps her "left" critique of Stein would carry some weight.

But a week before her anti-Stein article appeared, Aronoff held open the door to voting for Clinton in a video about "What Clinton has to do to win over Sanders Supporters."

Why not ask what Stein could do to win over Sanders supporters?

WHETHER ARONOFF is right or wrong in her answer to question one will, of course, be decided by praxis. Which brings me to question two: Would Gramsci support her argument?

Poor old Gramsci often gets dragged into political debates because he coined many clever sayings. But without, as it were, situating Gramsci "in the conditions of his own present," we risk reducing his insights into aphorisms. After all, the late, great Casey Kasem always reminded his American Top 40 audience to "Keep your feet on the ground and keep reaching for the stars"--which tracks very closely to Gramsci's famous advice to have "pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will."

So what was the context to the remark of Gramsci's that Aronoff quoted?

I'm not sure where she read those words, but to my knowledge, it was first translated into English in a footnote in Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. The quote is most often associated with a set of essays called The Modern Prince, in which Gramsci analyses the nature of ruling-class political parties and argues for the necessity of building a revolutionary workers party. In order to get past the prison censors that read everything he sent from his cell, Gramsci substituted the word "prince" for "party."

More background: Gramsci came to lead the Italian Communist Party in the early 1920s during a long political debate against Amadeo Bordiga, a fearless revolutionary and courageous anti-Stalinist, who was himself imprisoned alongside Gramsci for a time. Many other things aside, one of Gramsci's main criticism of Bordiga was that he tended to do what Aronoff accuses Stein of doing--that is, he emphasized that "politics is a battle of ideology, not power--no concrete plans required."

Thus, under Bordiga's leadership, the Italian Communist Party stood aloof from various concrete struggles, believing that capitalism would prove the communists right if only they kept their principles unblemished. Against this, Gramsci argued that the party had to form united fronts with other forces to fight for reforms, along the path of preparing for a revolutionary assault on capitalism.

Thus, Gramsci is often read as a "realist" or someone who was "willing to sacrifice principle for getting things done." This is how Aronoff seems to be deploying him.

But Gramsci's arguments must always be placed squarely in the context of his belief that the strategy of the united front was a more effective--to use that word again--path to building up a revolutionary workers' party in opposition to the ruling-class parties of his day, not as an excuse for cutting deals with them--never mind joining them!

HAVING SAID that, the Gramsci quote above is noted in a discussion of his method for dissecting the history of any given political party. He suggests that we must investigate:

[h]ow it comes into existence, the first groups which constitute it, the ideological controversies through which its program and conception of the world and life are forced... The history will have to be written of a particular mass of men who have followed the founders of the party, sustained them with their trust, loyalty and discipline, or criticized them "realistically" by dispersing or remaining passive before certain initiatives...The history of any given party can only emerge from the complex portrayal of the totality of society and State.

Based on Gramsci's method, what grounds do we have for faith in any effective approach to taking over the Democratic Party?

Are there powerful internal factions that are hostile to its ruling elements and its relationship to society and the state? Or are we mistaking those elements within the party who criticize it "realistically," as Gramsci hints, only in order to gently nudge it this way and that, without altering its fundamental allegiance to its corporate funders?

Gramsci next offers a useful conception of the relationship between various layers of political parties.

First, he says, there is the "mass element, composed of ordinary, average men, whose participation takes the form of discipline and loyalty, rather than any creative spirit or organizational ability."

Can you think of a better description of today's so-called "swing voters?" But this group also contains the mass of fed-up working-class people, of students, of people of color, women, LGBTQ people, etc.--people bearing the brunt of the crisis, but who have not yet, or have only sporadically, taken collective action in their own interest.

Second, we find the "principal cohesive element, which centralizes nationally and renders effective and powerful a complex of forces which left to themselves would count for little or nothing." In Democratic Party terms, this is the great gangs of professional politicians, fundraising bundlers, corporate lobbyists, financial and military CEOs, and public relations firms that constitute the upper echelons of the party's elite.

Finally, there is an "intermediate element, which articulates the first element with the second and maintains contact between them, not only physically but also morally." Fast forward to today's Democratic Party, and we can point to unions, student organizations, left-wing intellectuals and liberal publications which mediate between the alienated rank and file and the Democratic Party bosses.

HERE, GRAMSCI gives us the tools to evaluate the strength of the case for and against sticking with the Democratic Party or striking off to build a new party.

We might describe the two positions as follows:

Those who advocate the "realignment strategy" argue that the "intermediate element" must do what it can to organize the "mass element," in order to bargain with, reform or even replace the "principle cohesive element."

On the other hand, those who argue for an independent working-class alternative argue that the "intermediate element" must try to organize the "mass element," so that it can speak in its own interest and construct a political party of its own to fight in its own interests.

This methodological approach does not automatically end the argument, of course. However, Gramsci prefaces his remarks above with a description of why workers need their own party--not simply because a workers' party will have better platform language, but because the working class needs its own instrument to learn how to make a revolution:

The modern prince, the myth-prince, cannot be a real person, a concrete individual. It can only be an organism, a complex element of society in which a collective will, which has already been recognized and has to some extent asserted itself in action, begins to take concrete form. History has already provided this organism, and it is the political party--the first cell in which there come together germs of a collective will tending to become universal and whole.

Another term for that "collective will" is solidarity--the very opposite of the politics of the Democratic Party. Which leads me to believe that Jill Stein, Aronoff's objections notwithstanding, is entirely right to conclude that "you cannot make a revolution in a counterrevolutionary party." The Green Party falls far short of the sort of party the exploited and oppressed need to build for themselves, but in 2016, Stein's campaign points in that direction, as no Democratic Party campaign can.

In place of the long-term, patient approach needed to build up the forces of the still-weak left, Aronoff offers a half-panicked invocation that in order to "win," the left must start "infiltrating every level of government and playing every card in the deck."

For my money, Kenny Rogers was far more "Gramscian" when he counseled: "You gotta know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em." Reckless bluffs and all-in calls aren't the way to win at poker, and they don't work very well in politics either.