Marxism and the making of history

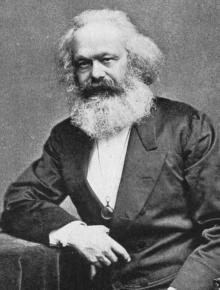

, author of The Meaning of Marxism, explains how Marx and Engels developed a theory that steered between two contending philosophical traditions.

EVER SINCE Marxism first emerged as a theory, critics have made the case that it is "economistic," "deterministic" or "reductionist"--that in putting forward the proposition that history is governed by laws, Marxism leaves no room for human beings to be anything but passive participants.

Marxism is fatalist, according to this interpretation, because it conceives of history as an inexorable process that takes place behind the backs of human beings and leads inevitably from one social system to another.

To bolster this claim, various quotes are offered. For example, in the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels wrote, "What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own gravediggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable."

Elsewhere, Marx wrote, "The windmill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam mill, society with the industrial capitalist"--a passage that gives the impression Marx thought changes in the methods of production automatically led to changes in social relations.

These critics usually counterpose Marxism to a more pluralist understanding of historical change. There are many "factors" that overlap and interrelate to determine the course of history, by this argument--and it would be wrong to "reduce" or make the "essence" of history revolve around economic development, classes or class struggle.

But from the beginning, Marx and Engels developed a theory that managed to avoid the extremes of seeing history as governed by unchangeable, iron laws, or history as something determined purely by human will.

Thus, the very same Communist Manifesto that stated "[the bourgeoisie's] fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable" also insists that history consists of a succession of class struggles--between different forms of "oppressor and oppressed"--which "each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes." That is, Marx and Engels thought two very different outcomes were possible, depending on the clash of social forces.

Indeed, for Marx and Engels, history wasn't something that happened behind the backs of people at all. As they wrote in 1845:

History does nothing. It "possesses no immense wealth," it "wages no battles." It is man, real, living man who does all that, who possesses and fights; "history" is not, as it were, a person apart, using man as a means to achieve its own aims; history is nothing but the activity of man pursuing his aims.

STILL, THERE is a clear gap, often a big one, between what people set out to do in the world and the outcome of what they actually do.

What accounts for this gap? For Marx, the contradiction was summarized by his statement that people "make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past."

When they became political activists, Marx and Engels were drawn to idealism--a philosophical tradition that viewed history as the product of new ideas about the world--because it was active and gave human beings a role to play in determining the course of their own development.

At the time, the contrasting school of philosophy, materialism, was passive, in that it believed that human behavior was shaped by circumstances. To that argument, Marx and Engels asked: But who created the circumstances to begin with?

As they developed their ideas, though, they began to be critical of idealism because it seemed to ignore the fact that things aren't doable simply because someone thinks they are. As Marx wrote in a work called The German Ideology:

Once upon a time a valiant fellow had the idea that men were drowned in water only because they were possessed with the idea of gravity. If they were to knock this notion out of their heads, say by stating it to be a superstition, a religious concept, they would be sublimely proof against any danger from water.

The point is simply that ideas aren't everything. Thinking about food doesn't fill our bellies, and without full bellies, it is very difficult to think. Somehow, you have to take into account the elements of the material world.

As Marx wrote later in the same book, it was necessary to recognize that:

it is only possible to achieve real liberation in the real world...by employing real means, that slavery cannot be abolished without the steam-engine and the mule and spinning-jenny, serfdom cannot be abolished without improved agriculture, and that, in general, people cannot be liberated as long as they are unable to obtain food and drink, housing and clothing in adequate quality and quantity. "Liberation" is an historical and not a mental act, and it is brought about by historical conditions, the development of industry, commerce, agriculture, the conditions of intercourse.

For Marx and Engels, the starting point to understanding human history was seeing humans as a species that produced their subsistence. How they produced it--what technologies they used and so on--shaped the kind of social organization they could develop.

In short, material and biological conditions of human development imposed natural constraints--successively overcome only by further developments of our productive forces--that constituted the boundaries of what was possible historically.

Once a certain set of social relations was established, they tended to act as a barrier to setting up different ones--and they only be overcome through the clash of competing social forces. To quote Marx again from The German Ideology:

[A]t each stage there is found a material result: a sum of productive forces, an historically created relation of individuals to nature and to one another, which is handed down to each generation from its predecessor; a mass of productive forces, capital funds and conditions, which, on the one hand, is indeed modified by the new generation, but also on the other prescribes for it its conditions of life and gives it a definite development, a special character. It shows that circumstances make men just as much as men make circumstances.

WHEN MARX and Engels began to move away from idealism, however, they did not move back to the old, passive materialism. Human beings did make history. However, they couldn't do it just as they pleased, but in conditions passed on from the past, over which they have no control.

Indeed, Marx and Engels were quite critical of passive materialism:

The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society.

The point they were getting at is: If people are products of circumstances, then how can those circumstances ever change? It would be necessary for some special group of people to somehow stand outside those circumstances and be puppet-masters, who reshaped things for everyone else. As Marx asked: "Who educates the educators?"

Ideas do change history, but only if they become material forces, supported by masses of people, and in conditions that made the establishment of new social relationships a real possibility. To put it crudely, the dream of a society that shares the wealth so that everyone can lead a decent life is merely a dream if the material means of producing that wealth aren't sufficiently developed so there is enough to go around.

For Marx, the connection between material circumstances and ideal change--the moment at which these two things begin to bridge the gap toward each other--is in social revolution. As he wrote, "The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice."

Naturally, the success of a revolution isn't a foregone conclusion. Quite the opposite--no amount of economic change at the base of society will in and of itself cause a transformation of social relations. That is only possible if enough people will it, and have the means to make that will a reality--including the means to overcome the physical resistance of defenders of the old order.

For Marx and Engels, this was the essence of politics. Without political power, they argued, the working class could not effect an economic and social transformation of society. But achieving political power wasn't possible without convincing vast numbers of people, through struggle and through their own experience, that another world is possible--that is, a vision of a new world.

In this respect, at the moment of revolution, ideas become supremely important. Economic relations constrain what is possible, but in the end, they don't decide whether or not we move forward. As the Russian revolutionary Georgi Plekhanov wrote:

Had Marx and Engels, from the very start of their political careers, not attached importance to the political and the "intellectual" factors and precluded their impact on the economic development of society, their practical program would have been quite different: they would not have said that the working class cannot cast off the economic yoke of the bourgeoisie without taking over the political power.

In exactly the same way, they would not have spoken of the need to foster class consciousness in workers: why should that consciousness be developed if it plays no part in the social movement and if everything takes place in history irrespective of the consciousness, and exclusively through the force of economic necessity? And who does not know that the development of the workers' class-consciousness was the immediate practical task of Marx and Engels from the very outset of their social activities?