Schools for struggle

The revolt of educators in West Virginia and the national walkouts and protests against gun violence have provided a real-life classroom for learning lessons of resistance.

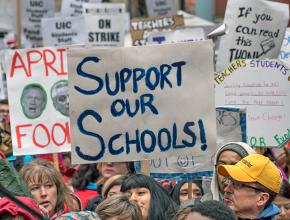

MARCH WAS the month when U.S. schools became the epicenter of explosive protest and solidarity--with teachers going on strike in West Virginia over wages and health care, and walkouts and protests across the country against gun violence.

Both of these struggles showed just how quickly a fightback can spread and inspire others to join in, but also how they can seemingly arise out of nowhere.

In many ways, this has been a signature characteristic of the Trump era: Energetic protests that burst into the spotlight in a world that feels like it's always on the brink of another atrocity of the Trump administration, another racist attack carried out by the right, another act of violence in school or elsewhere in society.

Another signature of the Trump era has been that more people are turning to solidarity as their defense against these myriad attacks.

The West Virginia teachers are a great example of this--educators and school workers in all 55 counties stood together to say "no" to state lawmakers who wanted them to settle for less than they deserved. The proud chant echoed again and again in the hallways of the state Capitol building: "Not one, not two, not three, not four, but 55 are at your door!"

Similarly, the students' campaign against gun violence--which led to thousands of school walkouts on March 14 and demonstrations around the country numbering more than 1 million, by most accounts--has mobilized youth from many corners of the country who are tired and angry about living in a world where violence is a fact of life.

The students who escaped the massacre at their school in Parkland, Florida, have made gun violence an issue of public discussion--but they've also created a platform for students from other schools and other backgrounds, who face different kinds of violence.

In addition to taking on the National Rifle Association and the politicians who pander to gun makers by resisting any regulation at all, students are talking about gang and police violence, the militarization of schools and the underlying causes of violence.

THE SPONTANEOUS and explosive nature of these fightbacks can teach the left something about the pattern of struggle in the Trump era and before. The strikes and protests may have erupted unexpectedly and spectacularly, but underlying them are years of conflict, discontent, and real but fleeting expressions of the desire for an alternative.

Since well before Trump, public schools have been the target of increasingly aggressive education "reformers," who front for corporations that seek to profit off the privatization of schools, while their defenders in government strangle the flow of revenue and resources to public education.

The Trump administration's Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is turning up the attack to 11. She's made it clear that her vision is for public education to be replaced with charter schools and vouchers.

But before that, the Democrats of the Obama administration went furthest down the road of school privatization. Outside Washington, local officials like Chicago's Democratic Mayor Rahm Emanuel starved public schools in poor and working-class neighborhoods--and then turned around and deemed them "failing" in order to promote charter schools and bash the teachers' union as the source of the crisis.

Politicians of both parties have invited corporate education "specialists" into public school classrooms to proliferate standardized tests, turning classrooms into places where the success--of students and teachers alike--is measured by mind-numbing, high-stakes tests. Teachers are blamed for trouble in the schools--with proposals to punish or reward them based on so-called "merit," as determined by test scores.

As a result, the teachers' struggles in West Virginia and other states like Oklahoma are about pay and benefits, but they are also about classroom resources, privatization and respect for teachers' hard work--all questions that educators in very different circumstances will recognize all too well.

Meanwhile, school privatization and the scapegoating of teachers are connected to attacks on students themselves, especially in poor and working-class public schools where Black and Latino students predominate. It is no leap at all for many students to connect the threat of mass shootings in schools with the increasingly militarized environment they experience.

Consider these factors together--along with a blustering president whose response to tragedy is to propose spending millions to arm teachers--and the explosion of protests and walkouts led by students isn't surprising either.

Nor is the fact that students have vowed to continue their campaign into April, with a national day of high school walkouts planned for April 20, the anniversary of the Columbine shooting.

But in the meanwhile, those energized by the protests will also be confronting the many questions that come up during discussions of guns and violence: the influence of the U.S. military machine, economic inequality, a history of racial violence and genocide. As we wrote in our editorial two weeks ago:

[A]fter March 14, it will be time for those committed to resisting the right, whether they just attended their first demonstration or have been active for many years, to draw lessons from the school walkouts and fit them into a wider resistance that wants a different world from one where Trump and the NRA call the shots.

THE RESISTANCE of the teachers is bringing some badly needed energy and important lessons to the labor movement.

The success of the teachers' strike in West Virginia showed the potential for others to use the strike weapon, even in a "right-to-work" state. Oklahoma could be the next stop, with educators preparing for an April 2 strike date.

The importance of individuals having the courage to take a stand and bring others along with them is being proven again in Oklahoma, as it was in West Virginia.

As West Virginia teacher Katie Endicott said in a Socialist Worker interview, "Someone has to start the spark, and the spark has to be fanned into a flame. But once it's fanned into a flame, you're not going to be able to put it out."

What happened in West Virginia fits with the long and often unpredictable history of the U.S. labor movement, in which there can be extended periods of seeming quiet interrupted by fierce battles, where there is no guarantee of victory.

SocialistWorker.org contributor Sharon Smith, author of Subterranean Fire: A History of Working-Class Radicalism in the United States, summed up the pattern in an interview for the upcoming paper edition of SW that will be published online later this week:

[A]s we can see from the experience of West Virginia, periods of "labor peace" don't necessarily indicate working-class satisfaction with the status quo. Usually, it is very much the opposite...From the outside, even though the labor movement seems calm, working-class lives have been upended to the point that the class struggle provides the only possible way to move forward.

For this or any struggle to advance past a certain point, it's important for those committed to it to draw the lessons of what has worked and what hasn't, in preparation for future battles.

Throughout four decades of existence, Socialist Worker and the organization that publishes it, the International Socialist Organization, have been dedicated to organizing support for workers' struggles--from the miners fights of 1977-78 to the Illinois War Zone battles of 1994-95, to the national UPS strike in 1997 and more--and drawing out the lessons for our movement.

Now, as Smith points out, the West Virginia teachers have "answered a question that has been haunting many of us--namely, after so many years, how can long-standing working-class traditions be transmitted to those who came of age in the last four decades, and have never had the opportunity to experience the highs and the lows of the class struggle that were once commonplace among workers?"

That answer came from an unexpected place--so-called "Trump country" dismissed by the media as a reactionary backwater. Similarly, socialists will be prepared to be part of whatever comes around the corner, in whatever arena of struggle it appears.

No one would have predicted that gun violence would inspire probably the most widespread school walkouts in at least a generation. Similarly, no one guessed that bitter anger at sexual violence and its perpetrators would take the shape of the #MeToo campaign and renewed activism around women's rights.

We don't know exactly how these struggles in our schools will shape up. But what we've learned already is that schools don't have to be places where corporate "reformers" like DeVos can make a buck off of privatization, where teachers are scapegoated, and where students live in terror of a mass shooting or are corralled like criminals under armed guards.

We've learned that students, teachers and their protests can start to transform schools into places where we can expect real learning, dignity and respect.